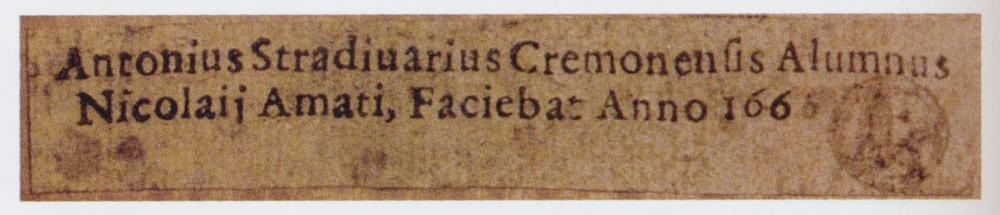

Any string player, or lover of music for that matter, has heard the name Stradivarius, a name synonymous with the violin. Many people think it is a type or brand of violin and are unaware it is actually the name of man, Antonio Stradivari, who lived from 1644 to 1737 in northern Italy. His instruments bear a label with the Latinized form of his name, Antonius Stradivarius, and his instruments are commonly referred to as Stradivaris or “Strads.”

In the following series of posts, we will explore some aspects of the life and works of the legendary Antonio Stradivari.

Who is Antonio Stradivari?

Antonio Stradivari was an 18th Century Italian luthier -craftsman of string instruments- who created many instruments in addition to the violins, violas, and cellos for which he is most famous. Today, about 650 of his instruments are known to survive; about 50 cellos, 20 violas, almost 500 violins and a handful of others- two guitars, one harp, two mandolins and a scattering of other instruments.

Where is Stradivari From?

Antonio Stradivari was born in northern Italy, in or near the city of Cremona, in the country’s Lombardy region. Learn more

We have to remember that Stradivari was not born into wealth or position- he was just another citizen making a living at his trade and his fame only grew to its current eminence long after his death. Most of what we know about him is the result of careful searching by investigators through records from church or municipal records. Births, baptisms, marriages, deaths, legal proceedings, wills, all yield precious facts about the great man. Census records and city records of the inhabitants of each house in a town would record all the inhabitants, including apprentices living with a master and where the apprentice came from. From this has emerged a great mystery about Stradivari- he does not appear as an apprentice to any of the violin makers working in Cremona at the time, and, because of other skills of which he demonstrated a mastery uncommon among violin makers, some experts believe he was trained as a woodcarver and came to violin making at an age later than the usual 12 or 13 year old apprentice.

When was Stradivari Born?

Stradivari’s precise place and date of birth has been debated by historians for years because no direct evidence supports the exact day and year of his birth. Learn more

No evidence of his birth and baptism has been located in any parish registers of the city of Cremona, and it is believed he was born in a nearby village. From later dated documents bearing his age it is now believed Stradivari was born in 1644.

When Did Stradivari Die?

Antonio Stradivari died on December 18, 1737. Learn more By the time of his death in his early nineties, Stradivari had become so wealthy that the people of Cremona would say “as wealthy as Stradivari” to describe a well-off citizen, and his death would have been a notable event. Stradivari had become famous all over Europe, selling instruments to the nobility and royal families. Today the quartet (2 violins, viola, cello) of instruments he made for the Spanish Royal family survives in the Palacio de Oriente in Madrid, Spain.

The Stradivari Family of Violin Makers

Antonio Stradivari founded a family business which three of his sons joined, but did not survive beyond them. Learn more

Antonio Stradivari was born in 1644, began his independent career as a violin maker in 1665. He had a total of 7 sons and 3 daughters with two wives.

He married Francesca Ferraboschi in 1667. Three sons were born to them:

Giacomo Francesco (b. 1671) and Omobono (b. 1679) joined the workshop.

Alessandro (b. 1677), entered the priesthood.

Francesca died in 1698, and a few months later Antonio remarried Antonia Maria Zambelli, the daughter of a prominent Cremonese. That union brought five more children into the world:

Giovanni Battista Giuseppe (b. 1701), did not survive his first year.

Giovanni Battista Martino (b. 1703) entered the workshop but died at the age of 24. His existence was only learned of in 1995 with the discovery in 1995 of the Last Will and Testament of Antonio Stradivari

Giuseppe Antonio (b. 1704), joined the priesthood

Paolo (b. 1708), became a cloth merchant

When Antonio died in 1737 it appears the Casa Stradivari held a mix of instruments that were ready for sale as well as others that were half-finished, evidently left uncompleted over the decades. It is recorded there were ninety one violins, two cellos and several violas, shown by dendrochronology to be from earlier periods of Stradivari’s work. It is believed Francesco and Omobono spent the next few years preparing these for sale. Omobono died just 5 years later in 1742 at the age of 63 and Francesco followed him the next year, at the age of 72.

Violin making had changed and there was much more competition in other countries. The public seems to have become more interested in the work of the Austrian Jacob Stainer. Paolo, the youngest and last surviving son of Antonio, the best part of 40 years to dispose of almost a hundred remaining Stradivari instruments, selling the last in 1779 to a dealer in Paris, which had become the musical capital of Europe. It there, starting around 1820, that musicians began to appreciate the special attributes of the work of Stradivari and his contemporaries, and the legend of Cremona began to grow.

Who was Stradivari’s Teacher?

Antonio Stradivari’s teacher is widely believed to be Niccolo Amati, the leading violin maker in Cremona at the time. The truth is a bit more complicated.

While more and more about the lives of other violin makers have been uncovered, Stradivari’s early life and training are quite obscure. No record of his birth or baptism has ever been found. And although there is a genuine label of 1666 claiming to be a student of Niccolo Amati, it is the only one known to exist, and it is not proof that he actually studied with Amati.

This is because copious civic census records of the Amati household exist, with detailed lists of the many apprentices, and Stradivari never appears in them. Apprentices almost always lived in the home of their master, the room and board being the only payment received while they worked to learn the trade. This is pretty conclusive proof he never lived in the home of Niccolo Amati as an apprentice. There may be some other explanation for this label, and for now, we just don’t know.

Another interesting fact is that the workshop production his early years is pretty slim- only about 20 instruments survive from 1680 to 1694. Even accounting for some of his output being lost or destroyed it seems to indicate he was doing other work as well. His local connections placed him in a world of highly skilled professional woodworkers- the landlord of the home where he lived with his first wife was a woodcarver, and as Cremona is a small town even today, it doesn’t take much to imagine how easy it might have been for a skilled man to find work.

Stradivarius – What Makes it Special?

Stradivarius violins, violas, and cellos are recognized the world over as among the finest examples of these instruments ever created. The tonal magnificence of his works makes them so prized that they sell for millions of dollars when purchased today, but they are also prized for their visual beauty.

Learn more

Antonio Stradivari was a man who had the good fortune to combine fabulous skills of design and workmanship, a tremendous work ethic, and a long, long life. Stradivari in his lifetime created instruments which were prized by all- from the working musician to the nobility and royalty. After his death in 1737 his probably had faded into semi-obscurity, and other makers had the limelight until about the beginning of the 19th Century. Several factors cooperated to make this beginning of the glorious fame his name has today.

Cremonese instruments had been making their way to Paris, which after 1750 had become the musical capital of Europe, and gradually began getting a reputation for unsurpassed tone. This was in part due to the development of music –orchestras growing larger, playing large symphonic works rather than chamber music, and performing in much bigger halls. A theatre built in 1781 is preserved in the summer palace of the Kings of Sweden at Drotningholm, and it only seats 200 or so people- a sizeable audience at the time. Around 1800 the first large halls began being constructed, with a capacity of 1000 people or more, and soon these were the norm. Around 1820 players began to realize that Stradivari instruments worked better than any others in these new conditions and the demand for his instruments grew.

There are several other makers who have made violins, or violas, or cellos which are prized as highly as Strads; cellos by Montagnana or violas by the Amatis, for instance. But no other maker has created as many great examples of all three as Stradivari. And the only other maker whose violins are equally prized is Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri, known to history as Del Gesu, made famous because Paganini preferred his instruments to Stradivari. We will explore his work in a future blog.

It is estimated he created nearly 2,000 instruments in his lifetime, of which about 600 survive today. The exact number is hard to pinpoint for many reasons- instruments are sold and then forgotten by the owner’s family, some are unknown and resurface, sometimes they are destroyed or lost. Carl G. Becker (the father of my employer Carl F. Becker) purchased two Strads in Italy in 1956. They were shipped home on the steamship Andrea Doria on the fateful voyage when it sank in July of that year. They are still in the wreck, 160 feet below the surface, near Nantucket Island off the coast of Massachusetts.

Stradivari was described by a musician that knew him as always dressed in white when he worked, and since he was always at work, he was always in white. He lived into his early 90s and worked right up until the end of his life. In 1983 I assisted in the repair of a Stradivari violin, the Muntz of 1736, on whose label Stradivari proudly wrote d’anni 92, indicating he made it when he was 92 years old. We can be grateful that this sublime genius lived so long, and was able to make so many great instruments.