Biography

From my earliest youth, tools and woodwork fascinated me. My parents presented me on my 8th birthday with a boy’s set of Stanley tools. No subsequent present ever gave me more joy, and the screwdriver and block plane from that kit survive on my workbench today. Music was another great love of my childhood, and playmates puzzled over my fascination with Beethoven’s 5th Symphony and Stravinsky’s Petrushka. After school and university, helping a friend build a house reawakened my passion for woodwork and I determined to make instrument making my life’s work. But how to make this happen was at first a mystery.

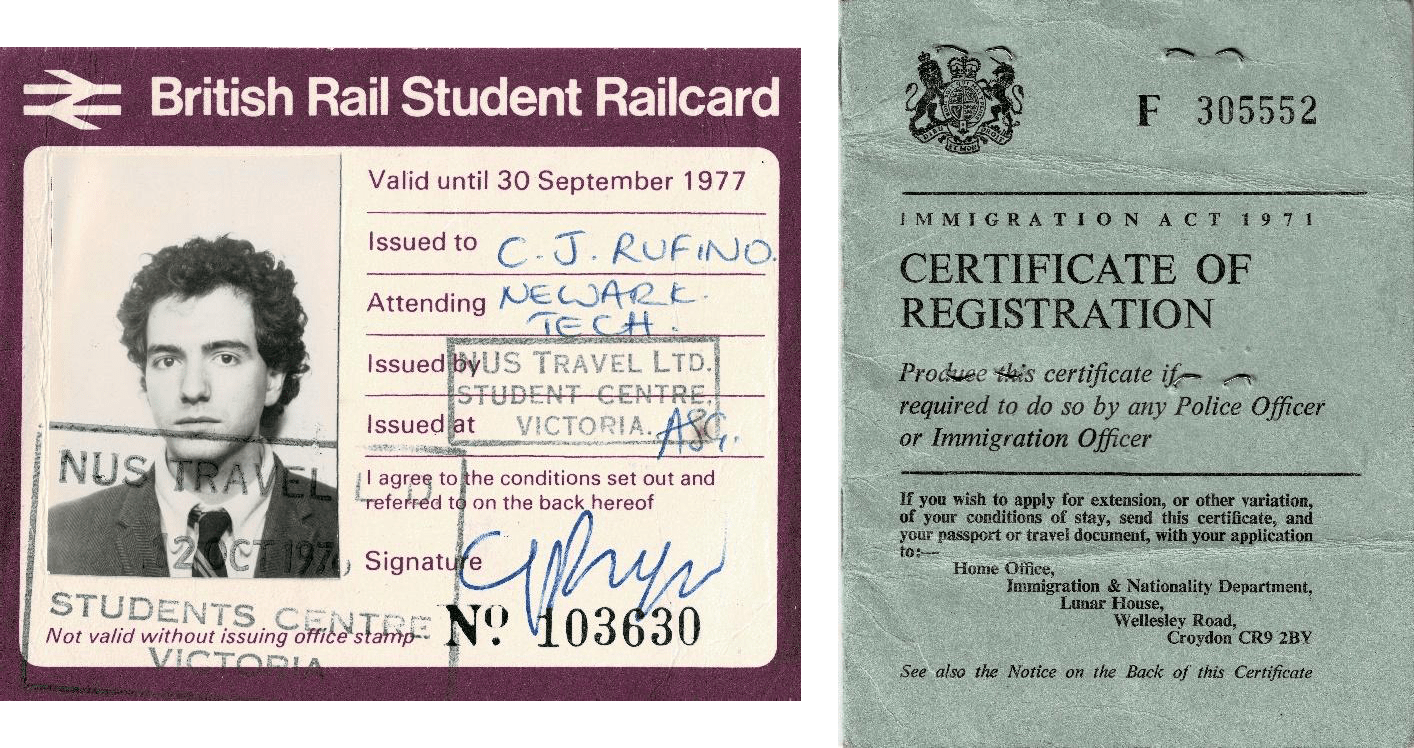

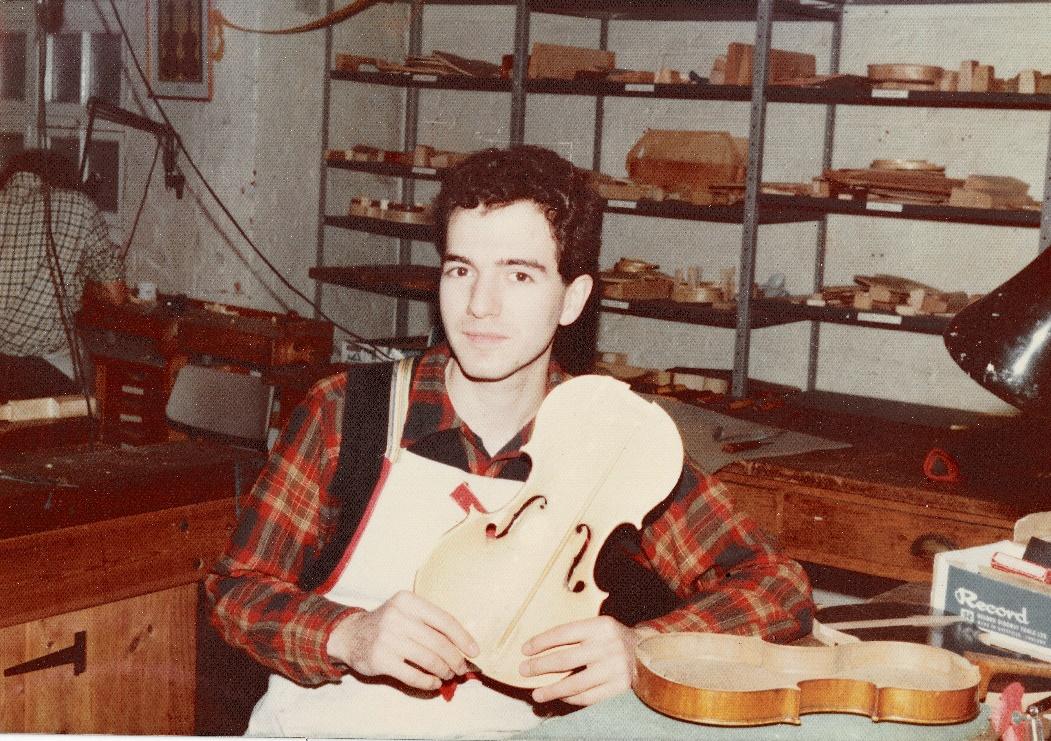

I had come to understand that only an uncompromisingly rigorous training would do, under true masters of their craft, which meant Europe. Thus, in September 1974 an ocean liner carried me to England to begin an apprenticeship at the Newark School of Violin Making in the English Midlands. For a kid from Manhattan it was a delightful change and my New York accent sometimes perplexed the locals as much as their accent flustered me. Over the next 3 years I was trained in new instrument making, repair, and varnishing.

Identity documents from my British sojourn

The Main Workshop at Newark

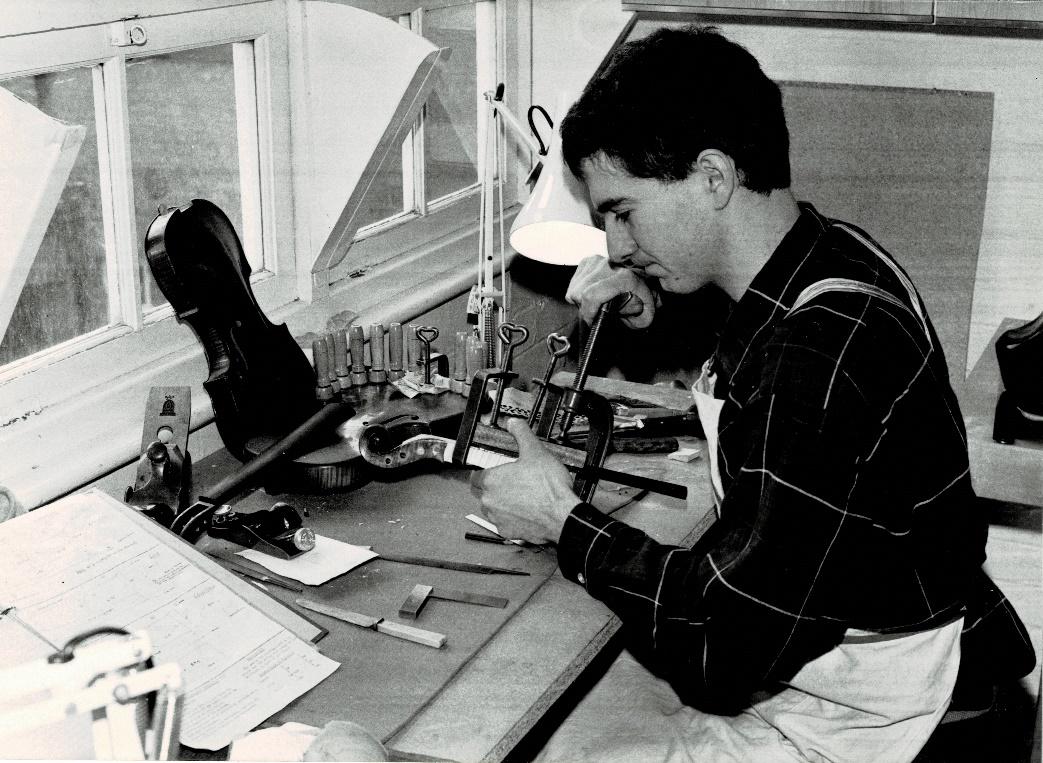

Restoring an old Violin

A new neck for a violin

Orchestra rehearsal- look closely to recognize some well-known colleagues

Our teachers were experienced and successful veterans of the London music world and it was a very exciting time to be an apprentice. For many years before, few young people had been drawn to this work, and we happy few were blessed with the enthusiastic support of illustrious London violin shops like W.E. Hill & Sons and J.& A. Beare. Always welcome to visit, we were able to study countless fabulous instruments. Christmas of 1975 found a small group of us assembled in the basement of the original Beare shop on Wardour Street, listening with rapt attention while Charles Beare spoke insightfully about the dozen or so marvelous instruments arranged on a table before us; Amatis, Strads, and Guarneris. We were able to compare a 1724 Joseph filius Andrea Guarneri violin with the 1741 Vieuxtemps of his son Del Gesu, examining the subtle improvements in the archings which made the son greater than the father. The earliest known Stradivari violin, the Serdet of 1666, rediscovered in a pawn shop in 1972 after being lost since 1910, was the most intriguing and unforgettable. Seeing these instruments intensified my desire to make instruments which would be admired centuries after I was long gone to a better life.

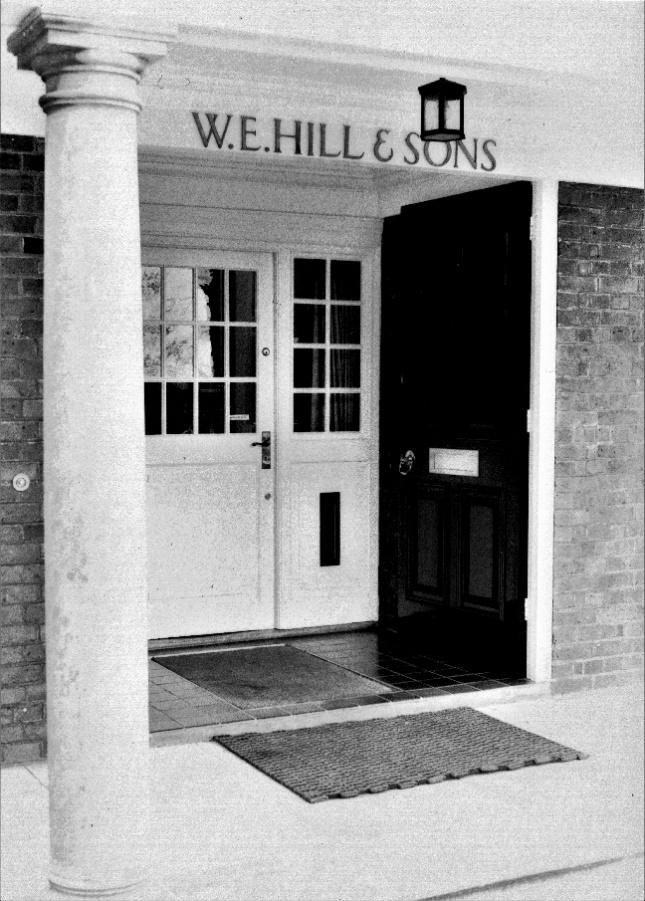

Another wonderful experience for us students was a chance to work a fortnight in the Hanwell shop of W.E. Hill and Sons, since Victorian times the home of great craftsmen. The shop dated to the late 1800s and was a storehouse of treasures going back centuries- a veritable museum.

The entrance to Hill’s

My workroom at Hill’s with a Guadagnini guitar for company!

The Hills flattered me with an offer of employment, but the pull of home was too strong and I returned to New York in August 1977 to join Nigo Nigogosian’s Stradivarius Studios on 57th Street in Manhattan.

Nigo at his workbench 1978. I sat right behind him, and he didn’t miss anything!

Over the next 3 years many challenging but happy hours were spent under the demanding eye of Nigo. While occasionally I would rue my earlier desire for an uncompromisingly rigorous training, the opportunity to study under such a master made it all worthwhile. He was born in 1910 in Istanbul to Armenian parents, came to Paris in 1929 for an apprenticeship with Marcel Vatelot, had his own shop for years in Istanbul, came to New York in 1958 working under Simone Sacconi at the celebrated Wurlitzer shop, and in 1972 opened his own shop again. Life on 3 continents spanning numerous cultures had given him a rich storehouse of wisdom and experience. A true artist, he had worked in the finest shops on the greatest instruments and would accept nothing but perfection from his shop.

1979 Nigo listens patiently to my opinion as we discuss a restoration

Nigo’s reputation for excellence brought many eminent performers to his shop who regaled us with unforgettable private performances. This was a period of refining skills and increasing my knowledge under a master who had seen and done more than I could have dreamed of just a few years earlier.

By the spring of 1980 I was ready for a change, and considered returning to England. But when Carl F. Becker of Chicago offered me a position, I thought I had died and gone to Heaven.

While his was a shop busy with repairs and restorations (just a few years earlier he had restored the immaculate Lady Blunt Stradivarius), Carl’s reputation as a restorer was equaled by his renown as a maker of new instruments. This was not only an unparalleled opportunity to focus again on new instruments, but to have great instruments of antiquity at hand to inform our work.

Carl Becker with one of his instruments

1981 Lessons with Carl

Every summer we would trek to the summer quarters in northern Wisconsin and remain until early November. There in a sunny, snug shop I was privileged to assist in the creation of a number of Beckers, make two instruments myself under his tutelage, and the legendary perfection of Carl Becker was drilled into me until it became second nature.

The workshop at Pickerel Lake in 1982. The 1736 Muntz is one of two Strads on the bench being restored.

In 1984 I returned to New York and established my own shop. Midwestern life accustomed me to more space than I could afford in the city, and I started working in my home in Huntington, Long Island. Reflecting on what I wanted to achieve in my work, I realized that I had had the great good fortune of studying with two masters whose artistry was focused on maximizing the comfort of the player and the tone of the instrument. I determined these would be the primary goals of my work as well.

Being home again was an opportunity to collaborate with Nigo again, and among other projects, I assisted him in establishing the first Oberlin Restoration Workshop in 1986 and in 1988 helped organize a tribute banquet for him in the Armenian Cathedral in New York.

The humble beginnings of the Oberlin restoration workshops

Carlos Arcieri, Nigo, and me bottom row at the very first Oberilin Restoration workshop in 1986

Time passes ever more quickly being self-employed, and among my greatest memories are being accepted to membership in the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers (AFVBM.org) in 1988 and the Entente Internationale des Maitre Luthiers et Archetiers d’Art (EILA.org) in 1994.

With Carl Becker at an AFVBM meeting in 1993

The opportunity to connect with colleagues from all over the world has been incredibly enriching and enjoyable, and has enabled access to rare instrument collections all over the world, from the Smithsonian Museum and the National Music Museum in the USA to the Musée de la musique in Paris.

Reunited after 40 years with a fellow student from Newark, Anne Houssay, at the Musée de la musique. That is one of the few remaining Octobasses made by Vuillaume in the 19th C.

The shop on Columbus Circle, 1999

In my working life, I have tried to continue the traditions in which I was trained, of instrument making at the highest level. The approbation of many fine artists playing my instruments has been my reward. Artists of the past, devoted to these same goals of instrument making, I hope the contribution of my own instruments may inspire future generations of makers. If we have never met, one day I hope you will have a chance to play one of my instruments.